|

|

Identify and assess the condition of and threats to your farm’s natural assets and pests

|

|

Include all aspects of your on-farm natural resources

|

|

|

Farm sustainability

Use a self-assessment tool (SAT) to

audit your farm’s financial, social and

environmental sustainability.

Tool 5.11 lists a number of SATs

which are general enough for any sheep

producer to use.

Identify and assess soil

erosion risks

Use tool 6.1 in Healthy Soils to assess

and record the land classes across your

farm. From your knowledge of the farm

and the land classes, identify the key

areas at risk of soil erosion and record

them on your aerial photo.

Three forms of soil erosion are reasonably

common on sheep properties:

- Sheetwash (sometimes called rill or

hillslope) erosion is the movement of soil

downslope by running water. The key

factors are rainfall intensity, groundcover,

slope length, gradient and soil erodibility

- Wind erosion is most common in

drier areas. Typically, areas subject to

wind erosion are exposed and have easily

transported, unconsolidated, loose and

fine sand-size aggregates

- Gully erosion is most common

in higher rainfall zones. Gullies

produce poor quality run-off and,

with streambank erosion, are the main

sediment sources across southern

Australia.

Maintaining and/or increasing

groundcover can prevent and/or reduce

the impact of these erosion processes. Set

goals for groundcover in each land class

on your farm using the benchmarks in

procedure 6.2 in Healthy Soils.

Use tools 6.2 and 6.3 in Healthy Soils

to measure groundcover at the sites with

highest erosion risk on your property.

Assess the salinity risk

The primary cause of dryland salinity

in Australia has been the replacement of

deep rooted/perennial native vegetation

with shallow rooted/annual crops and

pastures that use less water. A 1,000ha

farm receiving 500mm of rainfall has

5,000 megalitres of water to manage each

year.

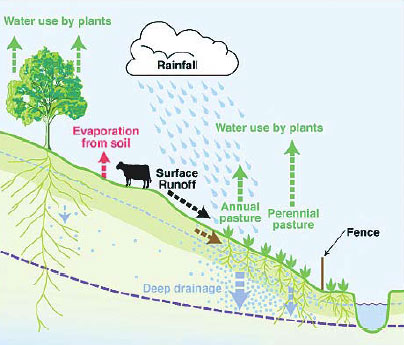

Poor management of the water cycle (see

figure 5.1) directly impacts on many

of our resource management issues,

including soil erosion, high nutrient

loads in rivers, soil acidity and dryland

salinity.

|

Figure 5.1 The ‘water cycle’ on a grazing property

(Source: Towards Sustainable Grazing – the Professional Producer’s Guide) |

The excess water (often called recharge)

not used by plants drains below the

root zone causing the water table to

rise. It may bring saline groundwater

up towards, and eventually into, the

root zone, somewhere ‘downslope’

(often called discharge). Sufficient salt

in the root zone can restrict or stop

plant growth. Contact your regional

natural resource management agency

(see signposts) to determine the risk of

salinity in your area. Use the following

tools to assess that risk to your grazing

enterprise:

- The pasture assessment techniques

in tool 7.6 in Grow More Pasture

to measure the perenniality of your

pastures. Compare your result with the

benchmarks in tool 7.6

- If areas are salty, tool 5.1 will help

rate salinity across your paddocks.

SALTdeck cards (see tool 5.10) will help

you identify the indicator species listed in

tool 5.1.

Water draining through the soil leaches

nitrogen and contributes to soil acidity.

Perennial pastures can assist in preventing

soils becoming more acid.

Productive pastures, profitable grazing

systems and improved sustainability are

all about efficient management of the

water cycle.

Assess the condition of

native vegetation

It is important to identify what native

species are present on your property

to inform future management actions.

Native pastures provide reliable (because

of their diversity) and low input

production while helping to maintain

healthy soils and ecosystems. Much

of Australia’s fine wool comes from

native pastures because they provide a

persistent, consistent feed supply.

Native grasses are more persistent when

allowed to recover after grazing, so that

rotational grazing/resting for at least part

of the year is an advantage.

Native pastures respond positively to

low rates of fertiliser, but higher rates

destabilise the pasture, with annuals and

weeds crowding out native perennials,

though this can be mitigated by grazing

management to some degree.

Species identification tools are not

included in this package but tool 5.10

contain many useful references and

links. Most regional NRM authorities

(see signposts) have tools, access to local

experts and information to help sheep

producers identify native species.

Several assessment and monitoring tools

are listed in tool 5.10. Use one of these

tools to quickly and simply assess the

condition of native bush, riparian zones

and native pastures on your farm and for

on-going monitoring.

Discuss and record what you would

like to see in your areas of native bush,

riparian vegetation and native pastures,

what changes could be made to protect

areas at risk (eg, make them larger,

denser, more diverse, etc), and when you

will address these risks.

Survey birds as ‘focal’ species

Birds have received more attention than

any other animal group when designing

landscapes for environmental outcomes.

Birds are a popular choice for several

reasons:

- Birds are mobile - they move across

the landscape at the planning scale of

hectares (paddocks) and kilometres

(properties)

- Birds are relatively easy to survey,

being abundant and visible during the

day

- Birds are placed well towards the

top of food chains - an ibis can eat 250

grasshoppers/day and a magpie can eat

40 scarab beetle larvae/day.

- A diverse range of bird species

inhabiting the ground, the understorey

layers and mature trees indicates the

remnant vegetation is healthy.

Native birds are perhaps the most

useful ‘indicator’ group. A farm with

a rich diversity of birds will also have

a relatively high diversity of trees,

shrubs, mammals, reptiles, frogs and

invertebrates. If the small birds are

missing, there is something wrong with

the habitat. Too many larger birds or

noisy miners indicate a lack of balance.

Use Quickchecks (see signposts) to assess

bird numbers and diversity on your

property. The tool accounts for the fact

that different parts of the farm will have

different bird groups, highlighting the

fact that a variety of habitats is required

across the farm.

Alternatively, keep a small notebook in

the ute and record birds (and/or native

animals) as you come across them in your

ordinary day’s work. All family members

can make entries in the notebook and

later add them to a master list.

Identify changes you can make to the

vegetation on your farm to improve bird

populations, and when you will make

them.

The Birdlife Australia website has ID resources, articles and publications.

Assess the prevalence of

weeds

Pests and weeds threaten both pasture

productivity and natural resources.

The threat posed to biodiversity by weeds

is ranked second only after land clearing.

Successful weed management is much

more than ad hoc weed control. It

is important to work out why weeds

are a problem on your property; set

realistic goals for both pasture and weed

management; undertake the appropriate

weed management practices on time,

every time; check whether your weed

management has been successful and

adapt your plan as needed.

This approach of Deliberation, Diversity

and Diligence is called the ‘3Ds of

Weed Management’. Each step has

key decisions and critical actions. Use

the Deliberation table in tool 5.3 to

compare a stocktake of your current

weed problems (species and density in

key paddocks) and agree on priorities for

action based on what you want the weed

level to be. Record what changes could

be made to weed populations on your

farm by when.

Assess invertebrate pests

Invertebrate pests, including insects and

mites, can significantly reduce pasture

productivity throughout the year.

Across Australia, Red-legged earthmite

(RLEM) infest 20million ha of pasture,

causing $200million damage to the wool

industry alone.

The first step on the farm is to correctly

identify the pest. Your local agronomist

can help you identify the species present.

Other sources of information include

CSIRO Entomology (see tool 5.10) and

State Departments of Primary Industries/

Agriculture.

Identify what you would like the pest

level to be, and what changes could

be made to reduce and keep pest

populations small.

It is important to choose the appropriate

tools to manage each pest, using an

integrated approach (integrated pest

management or IPM – see procedure 5.3) and to monitor the effectiveness of

your approach.

Different pests require different

management strategies. For example, redlegged

earthmite (RLEM) and blue oat

mite (BOM) look very similar but have

different lifecycles. This difference means

that the timing of pesticide spraying

using TIMERITE® (see signposts in

Procedure 5.3) works for RLEM, but not

for BOM.

Assess vertebrate pests

A variety of vertebrate pests affect sheep

farms across Australia, including:

- Introduced pests such as goats, deer,

rabbits, pigs, foxes, and wild dogs

- Native browsers such as kangaroos,

wallabies and wombats.

Many of the habitats that support native

animals and birds on farm also favour

the vertebrate pests. Individual sheep

producers and their families have to find

the balance that suits their situation.

Rabbits damage vegetation by

ringbarking trees and shrubs; prevent

regeneration by eating seeds and

seedlings; and degrade the land through

burrowing and reducing groundcover.

Selective grazing by rabbits changes the

composition of the vegetation.

Where rabbits have caused the slow

decline of, say, bulokes on roadsides in

western Victoria, there are fewer food

trees for species such as the red-tailed

black cockatoo that have declined as a

result, though clearly not from direct

‘competition’ from the rabbits.

The impact of rabbits often increases

during and immediately after drought

and/or fire, when food is scarce and they

eat whatever remains or re-grows.

2-3 rabbits/ha is sufficient to severely

depress the regeneration of native shrubs

and trees.

Spotlight transect counts (the number of

rabbits seen along a set route or transect)

are an accurate way to monitor rabbit

populations, though the number of

rabbits seen in the car headlights when

driving home provides a good enough

indicator of rising or falling rabbit

numbers.

Fox control can increase lamb marking

percentages by as much as 25% when

programs are implemented. In addition,

foxes are major predators of rabbits

(good) and small native mammals and

reptiles (not good).

While monitoring rabbit numbers is

useful on farm, monitoring fox numbers

is not. This is because of the highly

variable (and imprecise) relationship

between predator numbers and their

impacts on prey species, and because

with sheep, it is only at lambing that

predation is likely.

Identify the prevalence of vertebrate pests

and their location on your farm, what

you would like the pest level to be and

what changes could be made to reduce

and keep numbers down.

Audit stock water supplies

The majority of Australia’s livestock drink

from water that falls on the property.

A variety of measures can improve water

use efficiency in sheep grazing systems,

including creating additional watering

points and maintaining healthy soils to

minimise run off.

Healthy soil drives higher pasture

productivity and benefits the

environment through greater use of water

and nutrients in the paddock and less

risk of run-off, erosion and deep drainage

(see procedure 6.4 in Healthy Soils).

Like a feed budget (see tool 8.4 in Turn

Pasture into Product), tool 5.2 will

allow you to calculate how much water

you have, how much your stock need,

and/or how long a dam or water supply

will last.

Use tool 5.2 to complete a stock water

audit of the quantity, quality and

reliability of your stock water supplies.

A life-cycle analysis of water use in red

meat production found that it takes 103 -

540 litres of water to produce a kilogram

of red meat. This is in stark contrast to

50,000 litres per kg meat often quoted

(See: Red meat in the Australian Environment).

Climate change and

greenhouse gases

The Earth’s surface temperature depends

on the balance between incoming and

outgoing radiation.

The main greenhouse gases - water

vapour, carbon dioxide (CO2), methane,

nitrous oxide and ozone - absorb and

re-radiate much of the infrared radiation

released by the Earth’s surface.

All of these gases occur naturally. They

produce a natural greenhouse effect,

maintaining the temperature of the

Earth’s surface some 33°C warmer than it

would otherwise be.

Together, they make up less than 1%

of the atmosphere, which is comprised

mainly of nitrogen and oxygen.

Between 1750 and 2005, methane

concentrations rose by nearly 150% and

nitrous oxide by 18% (IPCC, 2007).

However, atmospheric methane

concentrations have remained relatively

stable since 2000, despite significant

increases in livestock numbers globally.

Australia’s livestock industry (including

dairy) produces 10.2% of Australia’s total

greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Most

of these emissions are methane from the

natural digestion process of cattle and

sheep. Energy generation represents 37%

of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate change impacts on sheep

enterprises

Australian sheep producers have always

dealt with a variable climate and its

associated droughts and floods. Climate

change scenarios suggest this variability

will increase.

In the sheep industry, climate change is

likely to impact on:

- pasture and fodder crops

- water resources

- wool production and quality

- animal health and reproduction

- land stewardship

- competition from other agricultural

activities

- national and international markets.

For example, farm input costs like

electricity, fuel and fertiliser will rise

when a carbon tax is introduced in

Australia.

Increased heat stress associated with

climate change could reduce the

reproductive performance of sheep in

areas where temperature and humidity

increases.

Vegetable fault and dust contamination

in wool could increase where pasture

composition changes, particularly if

weeds and bare ground increase.

Sheep producers now face not only

the continued challenge of managing

production of food and fibre, given

the variability in climatic conditions,

but the new challenges created by the

community’s desire to see reductions in

carbon emissions.

Sheep enterprise impacts on climate

change

A life cycle assessment of sheep meat

production in a southern Australian

production system measured total

emissions of 78 kg CO2 per kilogram

carcase weight.

Wool has excellent ‘natural’ credentials -

it is a renewable, biodegradable protein,

and more than 99% is produced in

extensive grassland terrain.

Use the FarmGAS Calculator (see

signposts) to estimate your farm’s annual

GHG emissions, both at the individual

enterprise activity level and for your farm

as a whole, and to examine the financial

impacts that different greenhouse

mitigation options may have on farm

business profitability.

Signposts  |

Read

Sustainable Grazing – a producer resource: this section of the MLA website provides a collation

of proven best practices for modern

grazing enterprises in southern Australia. www.mla.com.au/research-and-development/environment-sustainability/sustainable-grazing-a-producer-resource

Quickchecks: Natural Resource

Monitoring Tools for Woolgrowers

– tools to measure the health of your

pastures, soils, woody vegetation, farm

watercourses, paddock production levels

and birds. Download your free copy

(2.27MB) on-line at: https://www.wool.com/land/biodiversity/

The Potential Impact of Climate Change

on Woolgrowing in 2029: a report

commissioned by AWI that details the

effects of climate change on the wool

industry. Click here (in online version) to download the report (1.1MB)

Greenhouse Gas Emissions and the Australian Red Meat Industry: a report commissioned by

MLA on greenhouse gas emissions and possible abatement actions. Download here.

View

The Land section of the AWI website has information and case studies relevant to sheep producers on a range of natural resource management issues under the headings of soil, water, biodiversity and regenerative agriculture. Visit https://www.wool.com/land/

Regional NRM Authorities: critical

links for natural resource management

and funding – for access to all regional NRM

Authorities across Australia go to www.nrm.gov.au/regional/regional-nrm-organisations and click on your region.

The PestSmart Toolkit (www.pestsmart.org.au/) provides information and guidance on best-practice invasive animal management on several key vertebrate pest species including rabbits, wild dogs, foxes and feral pigs. Information is provided as fact sheets, case-studies, technical manuals and research reports. Also, view the PestSmart YouTube Channel (www.youtube.com/PestSmart/) for video clips on best practice control methods for pest animal management.

MLA Tips & Tools – a range of

publications are available covering native

vegetation, earthworms, biodiversity

benefits, birds and soil health. Get your

free copies of these MLA ‘Tips & Tools’

by:

Australian Good Meat website: MLA has developed the Australian Good Meat website to showcase the red meat industry's environmental and animal welfare credentials. The website informs consumers about the great work of Australian red meat producers and the high quality product they produce. It also provides a platform for red meat producers to share their story and demonstrate their commitment to best practice and continual improvement.Visit: https://www.goodmeat.com.au/environmental-sustainability/

Climate Change Information: Visit: www.mla.com.au and search for "Communicating Climate Change" for a range of publications.

Or order copies of MLA publications on

Climate Change by:

Managing Climate Variability

Research and Development Program:

a partnership of rural research and

development corporations has developed

and made available a range of practical

tools that help incorporate climate

information into farm business decisions.

Visit: www.managingclimate.gov.au/

Australian Farm Institute: the Australian

Farm Institute is an independent

organisation that conducts research into

farm policy issues to benefit Australian

agriculture. The Institute has released

four publications on different aspects

of emissions trading and its potential

impact on agriculture. You can purchase

these publications online by visiting:

www.farminstitute.org.au

FarmGas Calculator: Calculate the greenhouse gas emissions from your farm and compare the financial performance of different emission reduction activities that could be implemented in your business at: www.farminstitute.org.au/calculators/farm-gas-calculator

Birdlife Australia: visit https://www.birdlife.org.au/

Attend

The MLA EDGEnetwork® program is

coordinated nationally and has a range of

courses to assist sheep producers. Contact

can be made via:

Farmer’s guide to managing climate

risk: a NSW I&I PROfarm course

for sheep producers interested in

understanding weather and climate and

managing risk. For further information:

Apps

Weed ID; The ute Guide. Produced by GRDC. Available for iOS and Android. Designed to assist in the identification of most common weeds found in paddocks throughout Australia.

FeralScan (https://www.feralscan.org.au/) is a community website and Smartphone App that allows you to map sightings of pest animals and record the problems they are causing in your local area. FeralScan can be used by farmers, community groups, pest controllers, local government, catchment groups and individuals managing pest animals and their impacts. Available for iOS and Android.

Birds of Australia. Available for iOS and Android

|

|